There has been a rapid uptake of remote working and virtual consultation technology during the coronavirus pandemic, but that has left important areas of NHS IT untouched. Lyn Whitfield asks what has been happening to strategy, the digitisation of hospitals, and the development of the shared care records that will be needed in the post-Covid ‘reset’.

The novel coronavirus has altered fundamentally some aspects of the health tech landscape in the UK. As people started to become sick with Covid-19, trusts scrambled to make sure staff could work remotely and reconfigured their systems to triage and treat patients.

Outpatient clinics and primary care appointments moved to phone and video conferencing. While, more recently, there has been an effort to sort out telehealth and remote monitoring to keep people well, safe, and at home whenever possible.

A lot of this work has been impressive, but other aspects of NHS digitisation have been put on hold or at least overshadowed by the Covid response. So, some of the big questions that were being asked at the start of the year have gone unanswered or had less attention than they might have done.

Questions like: what is the strategy for NHS IT and who is going to deliver it? What is the plan for completing the roll-out of electronic patient records to the large minority of trusts that still don’t have them? And what is happening with the shared care records that will be needed to support the ‘reset’ world of integrated care and population health management?

What is the strategy?

Although it has not grabbed headlines, this has been the subject of some sustained attention by Parliament’s financial watchdog, the National Audit Office, and the MPs that it reports to on the Public Accounts Committee.

The NAO published a report on ‘Digital transformation in the NHS’ in May, which argued that many of the service’s systems are still “outdated and inefficient” and that it has “a poor track record” on improving things.

It noted that since the end of the National Programme for IT, which was “both expensive and largely unsuccessful”, the NHS has missed its major target to go “paperless” by 2018 and replaced it with a vague ambition in the NHS Long Term Plan “to deliver a core level of digitisation” by 2024.

NHSX published a ‘Tech plan for health and care’ in February, but the NAO pointed out that there is no implementation plan or metric for measuring progress. It’s also unclear how much money is required or where it will come from.

The government earmarked £4.7 billion for health tech from 2016-17 to 2020-21. But NHS England/Improvement thinks £8.1 billion will be needed to realise its digital ambitions, with £5.1 billion of that coming from central funding and £3 billion from trusts which, the NAO said, “may be unable or unwilling to find the money expected of them.”

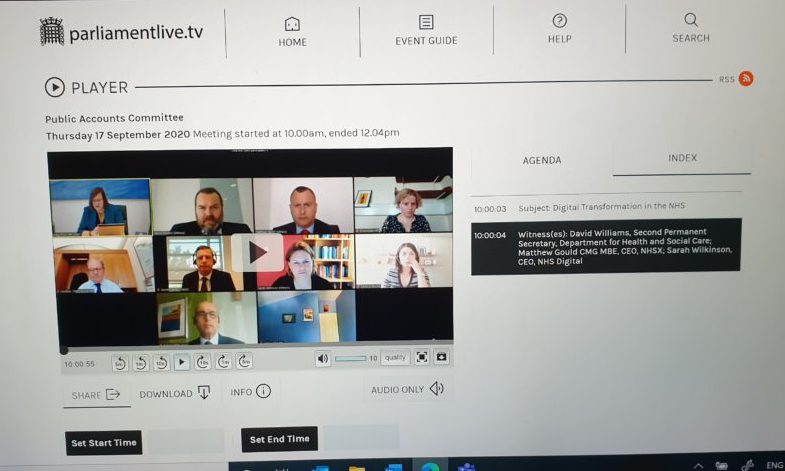

In a video-conferenced evidence session, PAC members explored additional challenges. MPs were concerned about the lack of clarity about how responsibility for health tech is split between the Department of Health and Social Care, NHS England/Improvement, NHSX and NHS Digital (the topic of a recent Highland Marketing board debate).

MPs also wanted to know what NHSX, which has never been established as a statutory body with auditable accounts, has been doing and spending – apart from creating versions of the NHS Covid-19 app, which will cost at least £35 million.

Unsurprisingly, when the PAC issued its own report on ‘Digital transformation in the NHS’ in early November, it reiterated the NAO’s criticisms before recommending some actions to get the DHSC and NHSX moving on addressing them.

The committee said it wanted the DHSC to write to it by March 2021 with some “realistic targets” for building on the gains made during the Covid-19 pandemic and to clarify who is responsible for what. It also recommended that it should publish an annual report on NHSX activity and spending.

The committee urged NHSX to publish an implementation plan, to work with NHSE/I to identify the organisations most in need of help, and to establish some cost/benefit criteria for the options open to them “so they can make the best choices about how to invest the limited funds available.”

Where are we on EPRs?

At base, what the NAO and PAC really want to know is how the digitisation of hospitals will be completed. In 2014, then-health secretary Jeremy Hunt tried to answer this question by asking a US expert, Professor Robert Wachter, to review the lessons of the National Programme for IT as the basis for further investment.

Wachter’s recommendations led to the creation of the global digital exemplar programme, which funded 26 acute and mental health trusts to become ‘world class’, defined as reaching Level 7 on the HIMSS EMRAM maturity model.

The idea was that the GDEs should help 24 ‘fast follower’ organisations to improve their own digital maturity, to develop ‘blueprints’ for others to follow, and promote their suppliers and deployment approaches through framework contracts.

However, the NAO argued in its May report that while the GDEs and their fast followers “report that they are improving in digital maturity”, there is “little evidence that they have succeeded in spreading best practice.”

In part, this may be because the programme effectively stopped with the arrival of Hunt’s successor, Matt Hancock, and the transfer of some IT responsibilities from NHSE/I to NHSX.

Since then, the government has run a Health Systems-Led Investment programme to make £413 million available to sustainability and transformation partnerships for IT of all kinds and a Digital Aspirant programme that found £28 million for a diverse range of projects at 23 trusts.

The NAO report suggested that even its auditors have struggled to work out where this money has gone. But it has not been enough to close the “wide variation” in trust spending on IT or digital maturity.

NHSX chief executive Matthew Gould has told numerous conferences that he wants to focus less on “the best” and more on “helping the rest to get better.” And he told the PAC that his organisation has taken some steps in this direction.

For example, he said it has focused on interoperability standards so systems can ‘talk to each other’ and on creating framework contracts to make it easier for them to procure compliant systems more quickly and easily.

He also said NHSX is working on guidance on ‘what good looks like’ and on ‘who pays for what’ to clarify what the centre will pay for and what providers will be expected to fund themselves. Gould suggested that this would address the NAO’s concern about trust investment by encouraging organisations to spend instead of holding out for national funding.

However, the PAC report noted that there is a long way to go on standards, since: “As of May 2020, only three of the ten sets of standards for achieving interoperability identified by NHS Digital were ready, and NHSX could not say when the others would be ready.”

At the same time, trusts do not seem to be making use of the flagship Health Systems Support Framework. The biggest EPR contract awards this year, from Manchester University Hospitals, Frimley Health, and Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS foundation trusts have all gone to Epic, which is not on it.

At the same time, the most interesting EPR approaches have arguably been announced by smaller trusts that are looking to develop modern ‘best of breed’ approaches using data platforms from companies like Alcidion and Better.

Gould insisted that NHSX would have been consulting on its tech plan this summer, if Covid-19 had not intervened. But for the moment, the NHS has no IT strategy, and it’s unclear how a rebooted consultation might take on board any lessons learned during the pandemic.

Even if the NHS had an IT strategy, the latest comprehensive spending review has been cancelled since the PAC hearing, leaving the NHS at the end of its Hunt-era IT funding with no capital budget for the coming year.

What next for shared care records?

In 2018, the GDE programme was followed by a local health and care record exemplar or LHCRE programme. This aimed to create integrated digital care records for populations of 3-5 million people, and to use the data they contained for integrated care and population-level analysis.

The analysis element was controversial, as the grand plan had some things in common with the discredited care.data programme. But five LHCREs were chosen to get the basics of information sharing in place or, in areas like Wessex, which uses the Orion Health platform, to start creating new patient pathways.

The NAO’s verdict on the LHCREs is that their performance has been “mixed”. Other views are more negative. In September, the Health Service Journal ran a story saying that a review for NHSX had concluded that the LHCREs had run into various problems.

These included uncertainty about the centre’s commitment to them and their future funding, a mismatch between their boundaries and those of emerging integrated care systems, and ongoing concerns about data sharing.

The HSJ story hinted strongly that the LHCRE approach would be abandoned so that healthcare systems could be given “more flexibility” to develop records on “whatever geography makes sense to them.” HSJ reported that at the PAC hearing, Matthew Gould confirmed this, while adding a target.

He told the committee that he wanted all 42 STP/ICS areas to have a ‘basic’ shared care record in place by next September. By basic, he appeared to mean sharing the data items in the Professional Record Standards Body’s core information standard, which covers information for direct patient care.

Data for research, analysis and planning appears to be out of scope. Gould also told the committee that NHSX is setting up another procurement framework and creating guidance for areas that need to move forward with IDCRs and that he hoped there would be funding for the plan “in due course.”

So, in this area at least, there is some clarity; although many of the details, supporting guidance and funding that healthcare economies and suppliers will be looking for has yet to be revealed.